In the Five Behaviors model, once a team has a foundation of vulnerability-based trust, mastering productive conflict becomes the next order of business. This model reminds us that conflict, rather than something to be avoided, is a healthy practice that drives innovation and helps create a commitment to team decisions.

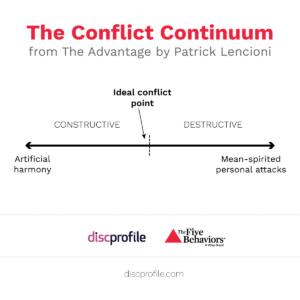

Patrick Lencioni is the author of The Advantage and The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. His work, combined with DiSC, powers the Five Behaviors model of cohesive teams. In The Advantage, Lencioni discusses a helpful image for helping teams navigate conflict: the conflict continuum. Lencioni explains the conflict continuum in this video.

On one end of the continuum is artificial harmony. On the other end is mean-spirited conflict fueled by personal attacks. There’s a sweet spot in the middle where healthy and beneficial conflict lives.

Most teams overvalue harmony

Some teams do operate on the right side of the continuum. However, says Lencioni, “the vast majority of teams we work with have far too little conflict.” Most teams spend all their time on the left side of the continuum, clinging to artificial harmony like they’re clinging to the edge of a swimming pool. They believe any move toward the other end is one step closer to nastiness. They seem to be getting along, but they’re not really being honest with each other.

Warning signs of artificial harmony

- Passive, indirect communication

- Boring meetings

- Back-channel discussions, frustrations aired privately

- Disengaged team members

- Lack of momentum, feeling of stagnation

- Opinions not solicited, in case this uncovers disagreement

- Time wasted protecting feelings

- Decisions that take too long; projects that drag on

- Problems that fester because they get glossed over rather than resolved

- Leaders that put a stop to disagreements rather than digging into them

Great teams embrace conflict

Teams who cling to harmony need to start taking steps toward the middle of the continuum, a little at a time, until they discover the line between productive and destructive. Lencioni says that “even the best team is going to occasionally step over that line,” but it’s not a reason to panic because “they’re going to learn that they can recover from that.” Great teams have the courage to live right at the line. And though they do their best not to step over the line, they realize that they can recover if they do.

Conflict-norming exercise for teams

If you want to help your team get more comfortable with conflict, try these steps:

-

The Five Behaviors model Define what you mean by conflict. Review the difference between destructive and productive conflict. Destructive conflict is mean-spirited and uses personal attacks. Productive conflict remains focused on ideas, encourages debate and disagreement, and addresses difficult issues instead of avoiding them.

- Talk about how engaging in conflict could help your team get better results. Ask for examples of times when the team valued artificial harmony over honest debate.

- Remember that teams gain fluency in conflict only when they have already established trust. Trust is the base of the Five Behaviors pyramid, and you can’t build a house from the top down. Review each team member’s conflict tendencies. An Everything DiSC® or Five Behaviors® assessment is a great tool for this.

- In collaboration with the team, choose one topic on your agenda that would benefit from more debate.

- Lay the ground rules for this exploration into conflict: no personal attacks, everyone should voice their opinion, etc. Remember, you all have (or should have) the same goal: getting the best results.

- As the discussion progresses, do what Lencioni calls “mining for conflict.” If you see someone disengaging, try to draw them out.

- Affirm the team when they’re doing well. Keep reminding them that team conflict is healthy and necessary for becoming a stronger team.

- Stay with it until the issue is resolved or everyone has committed to a decision.

- Debrief with the team about how it felt to welcome conflict.

- Repeat whenever you sense the team needs permission to engage in more conflict.

Each team member shows up to work with their own unique relationship with conflict based on their life experiences, their personalities, and their cultural and family views around conflict. No two teams are the same, and “that’s okay,” says Lencioni, “because there is more than one way to engage in healthy conflict. What’s not okay is for team members to avoid disagreement, hold back their opinions on important matters, and choose their battles carefully based on the likely cost of disagreement. That is a recipe for both bad decision making and interpersonal resentment.”

Once teams know how to navigate healthy conflict, there will be more commitment around decisions. This happens when everyone is able to voice their perspective. Once people know they’ve been heard, they’re more likely to commit, even if the decision made wasn’t what they were advocating for.